Life Interrupted: How a Stroke at Age 23 Led Me to My Life’s Calling

Share

a few years post stroke and you can still see my facial paralysis

At age 23, not long after graduating college with an elementary education degree, I was substituting and searching for the right district and school to begin my career. I lived at home in my mother’s apartment, trying to pay off school loans and save money before moving out on my own.

One late afternoon, after a full day of subbing, I went shopping and grabbed a coffee with a girlfriend. When I returned home, I wanted to show my mom the new pair of boots I had found for work at Nordstrom Rack. As I bent over to pull them on, I immediately felt strange. My mom thought maybe the coffee had affected me and suggested I eat some protein. She quickly whipped up a bowl of canned tuna fish—never my favorite smell or taste, especially not in that moment. To appease her, I tried to take a bite but couldn’t. Instead, I lay down on the couch.

My college boyfriend, Tom—who is now my husband of nearly 20 years—came over for dinner, as he often did after his work day. I tried to explain how my body felt— tired, nauseous, and just off. Tom called his father, a family practice doctor in Arizona, to describe my symptoms. When I spoke with him on the phone, it was difficult to put into words how my body was feeling. That evening, I was so exhausted, could not eat my dinner, and I went bed early.

The next morning, at 5:50 AM, my alarm beeped. I tried to raise my left arm to turn it off, but noticed my arm felt unusually heavy. I turned my body and used my right hand to do it. I got up and headed to the shower. I struggled while undressing, washing my hair, and holding things in the shower—but I said nothing to my mom. I was determined to push through. That day was important. I had been invited to substitute for a second-grade class whose teacher was moving to California, and the school was seeking a long-term replacement. It was an opportunity to prove myself and become their teacher for the remainder of the school year.

At breakfast, I could not eat as I continued to feel an icky feeling all over. I grabbed my lunch, kissed my mom goodbye, and drove 30 minutes south on the freeway to the school. I signed in at the office, found the classroom, and read through the substitute plans before calling my mom to let her know I still wasn’t feeling well. She encouraged me to eat and to call her again at lunchtime if I still didn’t feel right.

The students arrived, and I pushed myself to be my best. I made it through the morning plans of reading, writing, and computer lab, determined to show that I was the right fit for their class. At lunchtime, as promised, I called my mom and said I still felt off. She suggested I come home, but I refused to leave. I wanted this to be my new job.

After lunch and quiet reading time, I walked the students to P.E. class. On my way back to the classroom, I stopped in the restroom. When I looked in the mirror, I realized the left side of my face wouldn’t move. I also realized I had been dropping everything I held in my left hand; my entire left side felt like it had ten-pound weights pulling it down.

I walked into the school office, tears streaming. The secretary saw me and asked, “What happened? Is it the kids?” This class was known for their difficult behavior. My heart was pounding so hard I could hear it in my ears. I replied, “No, it’s me. Something’s wrong with me.”

I was immediately brought into the nurse’s office, where I shared the backstory— pulling on the boots the night before, the tuna fish, nausea, exhaustion—everything. She asked if she should call someone for me. Not wanting to bother Tom at his new job, I had her call my mom instead. At that moment, I still had no idea what was happening to me.

The fire department came, checked my vitals, and placed me on a stretcher to wheel me out. I was taken to Valley Medical Center, where the ER was so full that I was transferred to a bed in the hallway. A nurse briefly assessed me and said, “It’s probably Bell’s Palsy, you’ll be fine.” I didn’t know what that meant, but I clung to the words ‘you’ll be fine.’

Soon after, my mom, Tom, and my grandparents arrived. Hours later, I was moved to a room, where all the tests began—blood work, and a CT scan. That night, I fell asleep with my mom in the chair beside me. Over 24 hours had now passed since I first felt icky and we still were unclear what was wrong with me.

At 4 AM, a nurse woke me and my mom with the words: “You have suffered a stroke.” My mom began shaking, crying, and hyperventilating, nearly fainting. I sat there, staring—confused. A stroke? That was for old people. I was only 23.

At 7 AM, Dr. Heide, a neurologist, entered my hospital room. “I saw it right away,” he said. “A clot on the right side of your brain which is affecting the left side of your body.” He asked, “Do you take birth control?” to which I responded, “Yes. I even took it this morning.”

Dr. Heide began to explain what likely happened— a blood clot formed in my leg, exacerbated by birth control, traveled through an undiagnosed hole in my heart—called a PFO (patent foramen ovale)—and lodged in my brain. Tests confirmed both the PFO and a clotting disorder called Protein S deficiency, which increases the risk of blood clots, strokes, and pulmonary embolisms.

In the following days, I learned about my new reality: daily blood thinners, cardiology appointments, physical therapy, and a future without taking any hormones. I was also told I might never have children—depending on how things go with the blood disorder and heart defect. This was devastating to hear. Tom was there when the doctor shared this news, and I feared he might walk away as children were something we both wanted in our futures. Instead, he stayed, unwavering in his love and support.

My teaching dream had to be put on hold as I focused on recovery. Physical therapy helped me regain strength and mobility, and I eventually underwent a procedure to close the PFO, reducing my risk of future strokes. With time, I made strides and returned to the classroom to pursue my dream.

Beyond the physical challenges, I didn’t know how to process—or even acknowledge—my emotions about my stroke and the life-long implications it would have. I had not learned how to face something so overwhelming, let alone put words to my feelings and express them. I powered through recovery, ignoring how deeply the experience had shaken me. I didn’t know how to say, “I’m scared” or “I’m feeling lost.” I just kept going.

In teaching young children, I began to notice their need for developing social-emotional skills, such as self-awareness, fostering relationships, empathy, respect, and problem-solving. This reflection led me to realize that I, too, had lacked these vital life skills. I came to understand that acknowledging my emotions was just as important as my physical healing. Once I learned to identify, express, and process my feelings, I was able to truly heal.

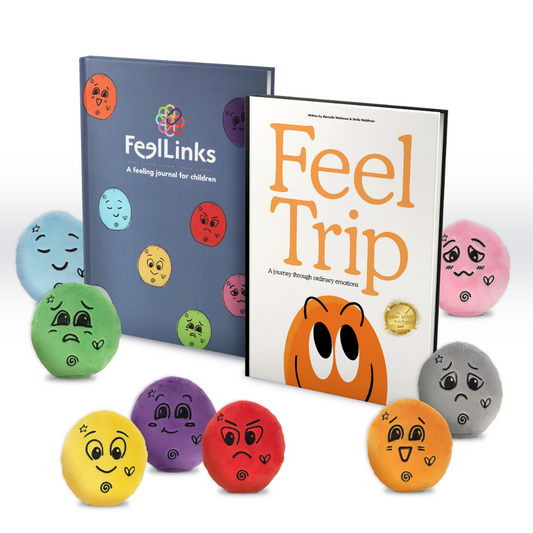

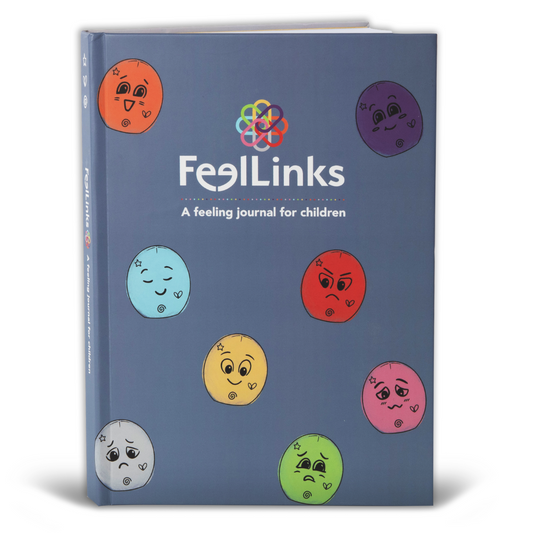

Now, 20 years later, Tom and I are parents to our two beautiful teenagers. I am the proud founder of FeelLinks (myfeellinks.com). I have combined my personal life experiences, teaching career, parenting experiences, education and the latest research, to create resources and teach parents, caregivers, school staff, healthcare professionals, and communities, how to support children in building emotional intelligence.

As for the residual effects of my stroke, I continue to have a droop on the left side of my face, which feels numb to the touch. It has taken me many years, along with a ton of hard work and repetition, to regain my strength and balance (as I used to be a dancer). I have taken over 1,400 Barre3 classes, and the exciting news is that, for all it has given me physically, mentally, and emotionally, I am proud to say I am about to embark on training to become an instructor.

I hope my story inspires others to face life’s challenges with courage and resilience, to understand and express their own emotions, ask for help from others, and support others when that are in need.

Facing an unexpected crisis at such a young age deepened my understanding of resilience—the ability to face life’s ups and downs, bounce back, and move forward in life. Emotional intelligence plays a critical role in this process. The 5 main areas that make up emotional intelligence are: self-awareness, self-management, social awareness, relationship skills, and responsible decision-making. These skills are important because they allow individuals to understand and manage their own emotions and effectively navigate relationships with others – leading to better communication, decision making and overall health and wellbeing.

Ultimately, this experience gave me a greater appreciation for life, a stronger sense of self, and a heart filled with kindness and compassion for others, along with the will to spread it far and wide.

Helping others learn the life skills I once lacked has become my purpose.

Thank you for reading my story...it's taken me over 20 years to write it out and I really do hope it inspires you.

xoxo Marcelle

3 comments

Marcelle, thank you for sharing such a powerful and deeply personal story. Your resilience and courage are truly inspiring. I can only imagine how overwhelming and life-changing this experience must have been, especially at such a young age. I love how you’ve turned something so challenging into a purpose that’s now helping so many others. It’s a beautiful reminder of the strength we can find within ourselves and the impact of emotional intelligence. Sending you so much admiration and gratitude for sharing your journey—this will undoubtedly inspire and support so many people. ❤️

Marcelle, you are so precious! I am so grateful you made it past such an event! I am have been a neuro nurse many years and have great passion to help prevent strokes. Thank you for sharing this. My daughter had emergency brain surgery this year at 21 years old. You were also so young. So very blessed are the righteous. You have great work to complete, girl!

Holy moly! I had no idea about your story and I can’t thank you enough for sharing it. I am moved and inspired by you and the life you lead. Marcelle, I can’t imagine how scary that season of life had to of been. It’s a true testament to how strong, resilient, and driven you are to overcome or achieve absolutely anything you set your mind to. I am better because I know you, and I feel so blessed to say that!